Less than a year after Stalin’s death, Soviet and East European newspapers published a lengthy text entitled “Theses on the Three-Hundredth Anniversary of the Reunion of the Ukraine with Russia (1654–1954): Approved by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union”1. The publication was a kind of summary of Ukrainian history written from a teleological point of view. The entire history of Ukraine before 1654 was interpreted as a preparation for the “reunion… of the freedom-loving Ukrainian people… with the Russian people in a single Russian state”, and all history after that date was presented in terms of transition from the “friendship of the two great kindred Slavonic peoples” to the “unbreakable friendship of the peoples of the USSR”. Although the “Theses on the Reunion” were to be accepted without question by Marxist historians, only in Ukraine were they – until recently – treated as unquestionable dogma, more weighty than the pronouncements of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin2.

The “Theses on the Three-Hundredth Anniversary of the Reunion” stressed repeatedly that “economic and cultural relations between the Ukraine and Russia… helped to bring the two kindred peoples closer together and had a beneficial influence on their cultures”. After the publication of the “Theses”, study of the “cultural links” between Russian and Ukrainians was officially declared to be one of the most important tasks of Soviet Ukrainian scholars. Soviet Belarusian scholars were charged with a parallel task. It is puzzling, then, that only two extant comprehensive monographs devoted to cultural contacts of the East Slavic nations during the early modern period of their history exist, and that neither belongs to Soviet historiography3. One, the opus magnum of Kostiantyn Kharlampovych, Малороссийское влияние на великорусскую церковную жизнь (volume 1; limited to late seventeenth and first half of the eighteenth centuries), was published in Kazan 1914. The second, a monograph by the British Slavist David Saunders, entitled The Ukrainian Impact on Russian Culture, 1750–1850, appeared in Edmonton in 1985. Both books are devoted to a later period, and both deal with the Ukrainian influence on Russian culture. In the Soviet Union, the Russian influence was consistently portrayed as beneficial, even charismatic, yet no one tried to produce a solid, detailed study of this cultural interaction. Propagandistic publications presented actual or imagined data about cultural contacts only as “preconditions of the reunion” or as instances of Russia’s disinterested assistance to her Slavic brothers. Such rhetoric accepted and repeated questionable information if it seemed vaguely to conform to the official line. Only in a few areas of study could scholarly standards be maintained. Popular among scholars in Ukraine, for example, were topics connected with the activity of the першодрукар (“first printer”) Ivan Fedorov (Fedorovych) in Ukraine and Belarus. Ideological authorities favoured these because the outstanding contributions of this Muscovite émigré to Ukraine’s cultural development were undeniable4. In describing the background of Fedorov’s activities, several Ukrainian historians used the topic to show the comparatively full cultural spectrum that existed in Ukraine prior to Fedorov’s arrival. This avenue of circumventing censorship was initiated by the most respected West Ukrainian historian, Ivan Krypiakevych. His short monograph Зв’язки Західної України з Росією до середини XVII ст. (Kyiv, 1953), its “ideologically correct” title notwithstanding, was replete with specific facts about economic and cultural conditions in Western Ukraine. His model was followed, with varying degrees of success, by several other historians5.

Soviet Russian historiography, which had much more freedom (at least, in dealing with the history of inter-Slavic relations), evidenced small interest in the cultures of Ukraine and Belarus and in the problem of Russia’s relations with them. The second half of the seventeenth and the beginning of the eighteenth centuries were the only period for which considerable Ukrainian and Belarusian influence was acknow-ledged. The balanced monograph of Mikhail Dmitriev on Reformation movements in Ukraine and Belarus may signal a change in this regard6. The exhaustive studies of Orthodox canon law by Iaroslav Shchapov also take into consideration ecclesiastical and cultural contacts among the East Slavic nations. Until recently, contacts between Ukraine and Russia were represented mainly as a bilateral process, not only in general courses and textbooks, but also in scholarly monographs. The same applies to studies of relations between Belarus and Russia. The broader context of these contacts was more often declared than explored.

The objective of this paper is to discuss some aspects of East European cultural geography that can illuminate the background of inter-Slavic cultural relations from the late fifteenth through the early eighteenth century. The concept of cultural circles (Kulturkreise), which until recently was readily dismissed by Soviet historians, is useful in this respect.

Until the end of the seventeenth century, the character of Russian culture was determined by its belonging to the realm of Eastern Orthodox Christianity in its specific post-Byzantine variant. Ukrainian and Belarusian culture, in contrast, began much earlier to attain a special character, with influences from both the Eastern and the Western Christian world. Outer expressions of this were the comparatively swifter “Westernization” of Kyivan Orthodoxy and, later, the appearance of the Byzantine-rite Catholic church. As a result, in some important cultural areas Ukraine and Belarus remained in the post-Byzantine Orthodox tradition, alongside Russia, the South Slavic nations, Rumania, and Greece, while in other respects Ukrainian and Belarusian culture were determined by contacts with Catholic and later also Protestant communities. The situation was made more complex by influences from Oriental cultures and, in the case of Russia, by contacts with the aboriginal peoples of Northern Europe and Asia. These contacts (which were especially evident in popular culture) will not be discussed in detail here, but it is essential at least to point out their importance as channels of cultural exchange.

Until the mid-seventeenth century, links between Ukrainians and Belarusians remained so close that in many respects their cultures were inseparable. Both Ukrainian and Belarusian authors contributed to the development of a “plain Ruthenian language” (проста руська мова), which functioned as the Middle Ukrainian literary language in Ukraine and as the Middle Belarusian literary language in Belarus and Lithuania. Among educated society in both Ukraine and Belarus there existed elements of a common to Ruthenian ethnic and cultural identity. I modern scholarly usage it is perhaps most correct to reserve the term “Ruthenian” to refer to those phenomena that were common both Ukrainians and Belarusians during the medieval and early modern periods of their histories. For example, the name “Ruthenian church” is rightly ascribed to the Metropolitanate of Kyiv, to which both the Ukrainian and Belarusian territories belonged.

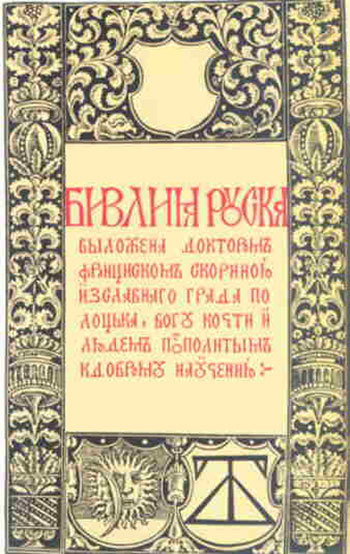

Initially, Belarus took a leading part in the common cultural area, as evidenced by the pioneering activities of Francis Skoryna (Franciscus Scorina de Poloczko Ruthenus) and of Belarusian cultural centres in Vilnius, Navahradak, and elsewhere7. Only later was a leading role assumed by Ukrainian educational centres in Ostrih, Lviv, and Kyiv. In the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, differences between Ukrainian and Belarusian cultural existed mostly on the level of popular culture and spoken language. Among other factors, the transfer of most of Ukraine from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania to the Polish Kingdom and the emergence of the Ukrainian Cossack tradition contributed to the further divergence of these two cultures (despite the fact that many Belarusians were active in the Cossack movement).

Ukrainians with Belarusians together with Poles, Lithuanians, and, to a lesser degree, other ethnic minorities (mainly Germans, Jews and Armenians), contributed to the emergence of a common cultural heritage in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. That culture is often referred to simply as Polish, but it was multinational in character and only with time did it become polonized, ideologically and to some degree linguistically8. The commonwealth’s culture shared in many Europe’s cultural movements, including humanism, the Protestant Reformation, the Catholic Counter-Reformation, and the Baroque movement in the arts and literature. The influence of the multinational Commonwealth as a whole on neighboring countries – Russia, Rumania, and Hungary – was perhaps even more important than the influence of any one constituent part of that Commonwealth.

Attention to the Western-oriented aspects of Ukrainian and Belarusian cultures provides a general perspective for speaking about their Eastern contacts. The concept of Slavia Orthodoxa as a supranational spiritual community, most clearly formulated by Riccardo Picchio, has been readily accepted by most Slavists studying medieval and early modern literature. Of course, it is understood that Orthodox Slavdom was only part of the broader spectrum of Byzantine and post-Byzantine (i. e. of the so-called Byzance après Byzance) cultural. The term “Slavia” needs more precise definition, because not only Slavic peoples but also Rumanians wrote and spoke Slavic languages (i. e., Church Slavonic, Middle Ukrainian, and Middle Bulgarian) in literature and administration. The word “Orthodoxa” is also imprecise, for Catholic of the Eastern Rite retained not only the Slavonic liturgy, but also Byzantine traditions in theology, ecclesiastical organization, architecture, painting, and music. The entire activity of the Eastern Christian churches in Europe can be defined as a sphere in which Cyrillo-Methodian traditions remained alive in church life and in all cultural activities connected with the church. Literary genres and artistic styles described as belonging to the Old Rus’ culture, in many cases, characteristic of that sphere. It should be added that the second South Slavic influence, which affected (although to various degrees) the entire East Slavic region, contributed considerably to the cultural uniformity of Orthodox Slavdom.

Slavia Orthodoxa was divided into two realms, that of the South Slavs and that of the East Slavs. Each of the three East Slavic peoples emerged mainly as a result of the consolidation of several tribes or, rather, tribal unions. Forerunners of the Ukrainians were such early Slavic ethnic groups as the Polianians, Severianians, Dulibians, Ulychians, Tivertsians, Derevlianians, and, probably, the Eastern Croats. At the same time, the culture of all East Slavs acquired some common features within the framework of the Kyivan Rus’ state. The Kyiv metropolitanate, which remained the East Slavs’ only religious centre until the early fourteenth century, contributed to the uniformity of church organization. The heritage of Kyivan Rus’ is erroneously referred to as “Russian” by historians who remain under the influence of the so-called traditional scheme of Russian history. Even today many historians underestimate the degree to which the many distinctive features of Belarusian, Russian, and Ukrainian culture had their beginnings the Kyivan Rus’ period. Some of these features became evident even earlier9.

The direction of cultural links in the late medieval and early modern periods was determined not only by cultural traditions, but also, no less importantly, by the political situation in Eastern Europe. Early modern Russian culture developed under the protection of the independent state known as Muscovy. Although its cultural relations with East and West never ceased, the Muscovite state’s ideological policy called for cultural isolation. In contrast, Ukrainians and Belarusians were deprived of statehood. Although the vast majority of them were Orthodox Christians, the Ukrainian and Belarusian nobility gradually converted to the Roman Catholicism of the hegemonic Polish culture and consequently, over time, became polonized. Burghers, Cossacks, and nobles who remained Orthodox considered the maintenance of their “fathers’ faith” crucial for preserving their religious and ethnic identity. Cultural contacts within the Slavia Orthodoxa helped to defend the cultural heritage that was associated with the golden age of the Rus’ nation.

Inter-Slavic and inter-Orthodox relations were symbiotic. In the Eastern Orthodox world, the only independent country was Russia. The small duchies of Moldavia (Voloshechyna, or the Volokh land) and Wallachia (Mutenia, Multany, Tara Romaneasca) remained semi independent. Naturally enough, in countries where Orthodox Christianity was persecuted (or humiliated), the Orthodox clergy regarded the Orthodox rulers of other countries as their protectors. For these rulers, rendering support to their coreligionists living in heterodox states was not only the fulfillment of their Christian duty, but also a tool of state policy. During the Polish and Swedish interventions in Russia at the beginning of the seventeenth century, Orthodoxy provided ideological justification for the patriotic movement. Very soon afterwards, however, the “defence of Orthodoxy” began to serve as a slogan justifying the expansionist policy of the Russian tsars. The worsening condition of Orthodoxy under non-Orthodox administrations provoked the emergence of political forces seeking the protection of Orthodox monarchs or even the full domination of these monarchs over them. In most cases, the common identity of faith was the basis of such movements, rather than the movements’ “external manifestation”, as some Soviet historians have suggested10. Several Ukrainian religious confraternities, including the influential ones at Lviv and Kyiv, initiated contacts with Muscovy in an effort to counterbalance Polish domination. At the same time, some hierarchs and other public figures oscillated between subordination to the Polish Crown and sympathy to Orthodox Muscovy. Their contradictory declarations of loyalty confuse contemporary historians, who are inclined to take at face value declarations that are in agreement with established scholarly concepts. What is not taken into consideration is the fact that in many cases, contacts with Muscovite authorities helped Ukrainian Orthodox public figures to exert political pressure on Polish authorities – or, at least, to enhance their political prestige.

During the initial stages, cultural contacts within Slavia Orthodoxa developed mostly in the religious sphere, whereas the contacts of Orthodox peoples with the Western cultural heritage were more extensive in the secular domain. The circulation of manuscripts, icons, and various artifacts between Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia occurred as part of the circulation of such items throughout all Slavia Orthodoxa. The majority of circulating manuscripts were liturgical books, but another important component of the exchange was canonical and apocryphal religious literature, sermons, and hagiography. Original Literature including chronicles, letters, and secular texts of a practical nature was less frequent, but was nonetheless interesting as evidence of cultural creativity. What traditional texts were exchanged was determined mostly by the activities of monasteries, bishoprics, and other ecclesiastical structures. The same can be said about the exchange in the field of religious art. Although church architecture developed independently on the whole, the export of icons from Muscovy to other Orthodox countries represented an area of important interchange.

Cultural contacts in the secular sphere developed mostly in the context of economic and political relations. Recent studies suggest that some linguistic parallels reflect the character of such cultural contacts. For example, the Russian word государство (from государ) derives from the Ruthenian господарство (from господар). In turn, the title of the grand dukes of Lithuania, государ і дедіч, probably derived from the identical titles of the princes of Galicia and Volhynia (dominus et heres, or господар і дедіч)11. The study of cross-influences in the sphere of public administration, law, and manners and customs is only in the initial stages.

Cultural exchange between Russia and the Orthodox territories of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth received new impetus from intellectuals who fled from persecution in Muscovy to comparative freedom in Belarus, Lithuania, and Ukraine. Examples include Starec Artemii in 1554 or 1555, a group of Muscovite heretics in the late 1550s, and Prince Andrei Kurbsky in the mid-1560s. These people contributed to the popularity of works by Maksim Grek and writers of his circle. The Muscovite émigré Ivan Fedorov was instrumental in establishing the first printing shops in the Ukrainian centres of Lviv and Ostrih.

Changes in cultural patterns contributed to the appearance of new forms of cultural contacts and to the narrowing of the gap between religious and secular cultures. In Ukraine and Belarus the process began much earlier than in Russia. Initially, Latin-oriented and traditional cultures developed mostly along parallel lines. The reciprocal modification of the two traditions facilitated their coexistence and, to some degree, mutual tolerance, in a milieu where East and est met. The main problem was how to adapt traditional cultural values to new social and cultural trends. That was undertaken in framework of new institutions such as confraternities and the humanist schools. The first establishment that set out to synthesize the local, mostly religious, Slavo-Byzantine tradition with Western secular and religious cultural trends was the Ostrih Academy, founded in 1577 or 1578. The first trilingual, “Greek-Latin-Slavonic” school was created there. Its very name reflected not only the languages to be studies there, but also the more general tendency to combine native culture with the Greek and Latin cultural heritages. Later that orientation was adopted by the Kyiv Mohyla collegium, and through that avenue the concept of “Greek-Latin-Slavonic” learning made its way to Moscow.

Whereas the Ostrih Academy and the confraternity schools initiated the movements towards combining post-Byzantine and Western cultural models, Peter Mohyla and his circle not only firmly accepted Western educational patterns, but also implanted into Orthodox theology some important elements of Catholic thought. As Aleksander Naumow has rightly pointed out, of less consequence is the degree to which pure Orthodoxy was contaminated: most important is the fact that the adaptation of tradition to the new reality was the only way to survive while preserving links with traditional culture12.

In Muscovy, the Westernization of Ukrainian Orthodoxy was watched with suspicion as long as the cultural orientation of the tsar’s state was determined almost exclusively by conservative circles. Later, when promodernization trends took a firmer hold in Russia, the attitude toward Ukrainian and Belarusian innovations became more sympathetic. The direct contacts of Russian with Catholics and Protestants were instrumental in promoting the slow process of cultural secularization. In religious affairs, innovations were more palatable when introduced not directly, but through the intermediacy of Ukrainians and Belarusians who had already modified foreign cultural models and adapted them to Orthodox traditions in some degree. Of course, the religious spheres cannot be neatly separated, and in both areas, direct as well as mediated contacts were in evidence.

The contacts of Ukraine and Belarus with Russia have some typological similarities with their Moldavian contacts. In the early period of its history, the Moldavian principality inherited some social and political institutions and cultural models from the Galician-Volhynian principality. The Middle Ukrainian language of Moldavia’s charters was a continuation of the language of West Ukrainian administrative acts. Ukrainian manuscripts penetrated onto Moldavia, and the code of ecclesiastical low used there and in other Rumanian lands was accepted from Volhynia. later, the situations was reversed: the Moldavian princes (господарі) assumed the role of protectors of West Ukrainian church institutions. The ornamented manuscripts produced in Moldavian scriptoria became very popular in Ukraine. The influences of Balkan stylistic trends in art and literature often reached Ukraine through Moldavia. At the same time, Ukraine continued to play the role of intermediary in the advancement of Western influences in Moldavia13.

In the second half of the seventeenth century, cultural exchange between Russia and Ukraine became more regular. Although the Moscow patriarchate eventually subordinated the Orthodox church in Left-Bank Ukraine, cultural leadership remained in the hands of the Ukrainian clergy. The Kyiv Mohyla collegium exerted a tremendous influence on ecclesiastical life and the educational system in Russia. Only some aspects of this influence have been studied in detail – among them, academic courses in rhetoric and poetic and school theatre14. The activities in Russia of Symeon Polotsky, Teofan Prokopovych, Stefan Iavors'kyi and their numerous Followers contributed to the dissemination of Kyivan cultural achievements. These scholars acted through the official structures of the Russian state and Orthodox church. No less important were influences on ordinary society, including the lower clergy. Official circles invited contemporary Ukrainian scholars and educators to work in Russia. The Old Believers, on the other hand, turned to the heritage of the Ukrainian and Belarusian thinkers of the former period, such as Stefan Zyzanii, Ivan Vyshens'kyi, and Zakharii Kopystens'kyi15, as is evident from numerous copies and translations of their works.

During, the late seventeenth and the eighteenth centuries, the cultural map of Eastern Europe changed dramatically. Russia’s upper classes were Westernized almost forcibly through to russification by the Russian government, including the subordination of the Kyiv metropolitanate to the Moscow patriarchate, ukases (issued in the 1720s) forbidding Ukrainian publisher to print anything that differed from Russian publications, and the centralization measures of Catherine II and her administration. In Right-Bank Ukraine and Belarus the nobility was eventually polonized, and the Ruthenian language gave way to Polish in many spheres of public life and culture. Nevertheless, the Kyiv Mohyla collegium continued to influence the development of culture in all of Ukraine and in parts of Belarus. Many teachers were an important channel between the humanist culture of the educated clergy and the folk culture of the peasant, the Cossaks, and most of the burghers. The existence of the autonomous Ukrainian Hetmanate and the acceptance of the Cossack tradition throughout Ukraine contributed to the further development of distinctive features in Ukrainian culture as compared with Belarusian culture. Ukrainians, especially those from the Hetmanate, became known in the West as the Cossack nation. On the other hand, not only Ukrainians, but also Belarusians were involved in cultural activities in Russia. Many Ukrainians and Belarusians were instrumental in promoting Petrine reforms.

Most Russian historians of pro-Western orientation have evaluated the Ukrainian and Belarusian impact on seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Russian culture very positively. Other Russian scholars, especially those with Euro-Asian or neo-Slavophile connections, connections, considered Ukrainian and Belarusian influences to have been disastrous for the identity of “Mohyla’s internal toxin” was “even more dangerous than the union with Roman Catholicism”. He condemned Stefan Iavors'kyi, Dymytrii Tuptalo, and other clerics education in Kyiv not only for their acceptance of Catholic theological ideas and Latin language, but also for their affinity to the European Baroque. Consequently, Florovsky deplored the fact that, in Prince Trubetskoi’s words, the culture of post-Petrine Russia was in many respects “a continuation not of the Muscovite tradition, but of the Kyivan cultural circle”16.

If Russian historiography is divided on this point, Ukrainian and Belarusian historians are united in their enthusiasm for the role played by Ukrainians and Belarusians in the “Europeanization of Russia”. In most cases they underestimate the extent to which the Ukrainian influence on Russian culture facilitated subsequent Russification. The Ukrainian and Belarusian cultures became most vulnerable to Russification once their cultural development lost momentum owing to most unfavorable political conditions17. The imperial discrimination against Ukrainian cultures was devastating not only in its direct effects, but also because it provoked cultural isolation and populist provincialism in the cultural life of the submerged nations. As far as Russian culture was concerned, the abyss between popular and elite cultural life contributed to the superficiality of the “Westernization” process.

Despite differences in speed and form, all East European nations were involved in general European trends. In most of Europe, the movement toward secularization of culture became unmistakable beginning with the last decades of the eighteenth century. Change was so profound that the late 1700s had much more in common with the next century than with the immediately preceding years of its own. The benefits of cultural change were argued by exaggerating the dark side of the pre-reform situations. Thus, the secularization of culture was often accompanied by a depreciation of the non- secular culture that preceded it. Nineteenth century rationalists continued to be influenced by such concepts, which sowed the ground for the quest-rational condemnation of religious culture after the 1917 revolution. Under the ideological pressure of official Soviet atheism, this attitude reached virtually grotesque forms. The current revival of interest in national heritage has also brought a tendency to idealize all old cultural traditions.

The development of secular culture in the later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries lead to the break of continuity in cultural development of social elites. Initially, no abrupt break occurred on the level of popular culture among the peasants nor among the traditionalist burghers. Subsequently, the situation was reversed. Peasant culture gradually began to lose its organic links with medieval traditions, whereas the resuscitation of those traditions was taken up by intellectuals. The modern generations values the traditional culture as possessing not only theoretical, but also practical importance.

Unfortunately, studies of Slavic cultures and of inter-Slavic cultural contacts have too often been influenced by political or ideological factors18. It is perhaps appropriate to conclude these sketchy remarks by expressing the hope that in the future, historians of East Slavic culture will be able to carry out their research without such hindrances.

Друкується за: Ярослав Ісаєвич, Україна давня і нова. Народ, релігія, культура. Львів, 1996. С. 198–213.

- I cite the official Soviet translations of the original Russian text into English, published in Moscow in 1954. A reprint appears in J. Basarab. Pereiaslav 1654: A Historiographical Study. Edmonton 1982, pp. 270-88.

- The well-known Ukrainian scholar Mykhailo Braichevs'kyi was harshly persecuted for trying to show that even from a strictly Marxist point of view, the concept of “reunion” was nationalist rather than internationalist.

- I exclude textbooks, so-called collective monographs, and books that, owing to their low scholarly level, are examples of “historiographical noise” rather than works of historiography. On the topic of relations between Ukraine and Russia, the former category includes Д. Мишко. Українсько-російські зв’язки в XIV–XVI ст. Київ 1959.

- For a discussion of the controversial issue of whether Ivan Fedorov was a Russian origin or, as Evgenii Nemirovsky suggests, a Belarusian émigré to Moskovy, see Я. Ісаєвич. Літературна спадщина Івана Федорова. Львів 1989, с. 29-30.

- Perhaps the best example is the monograph by Ф. Шевченко. Політичні та економічні зв’язки України з Росією в середині XVII ст. Київ, 1959. Much less successful in this respect were the chapters on culture (including my own) in the collective monograph, Дружба и братство русского и украинского народов. Т. 1. Киев 1982. The fact that the book appeared during a period when ideological censorship was particularly harsh is only a partial explanation. Historians who became accustomed to using ideological formulae as a kind of smoke-screen later applied the same formulae haphazardly – an attestation to the decline in the level of historical consciousness. Of those who wrote in official publications only a few retained their integrity.

- М.В. Дмитриев. Православие и реформация: Реформационные движения в восточнославянских землях Речи Посполитой во второй половине XVI в. Москва 1990.

- See Ф. Скорына і яго час. Энциклапедычны даведнік. Мінск 1988; Е. Л. Немировский. Франциск Скорина. Жизнь и деятельность белорусского просветителя. Минск 1990.

- A transitional phenomenon was the appearance of individuals, mostly among the nobility, who combined loyalty to the Polish state with identification with both “general-Commonwealth” culture and their Ruthenian cultural heritage. See F. Sysyn. Between Poland and the Ukraine: The Dilemma of Adam Kysil, 1600–1653. Cambridge, Mass. 1985.

- I discuss the role of the Kyivan heritage in Ukrainian cultural history elsewhere: see the Proceedings of the Conference of the Republican Association of Ukrainian Studies, held in Kyiv in December 1990 (in Ukrainian, forthcoming).

- The study of Belarusian, Russian, and Ukrainian theological thought in the context of both Orthodoxy and Catholicism is unjustifiably neglected.

- А. Золтан. К предистории русского государь, Studia Slavica, Budapest 1985, vol. 29.

- A. Naumov. Zmiana modelu kultury a kwestia ciągłości rozwojowej, Zeszyty Naukowe KUL, 1984, nr 4, s. 31.

- During some period, contacts with Moldavia were extremely important for Ukraine. For instance, the interior of the cupolas of the Dormition Church built by the Lviv Confraternity has three relief representing Moldavia’s state emblem, but only one of the Muscovite emblem. This reflects the degree of assistance received from the two countries for the construction of the church. Of course, in general, the Muscovite church and state were much more important to the Ruthenians than was the Moldavian church and state.

- P. Lewin. The Ukrainian School Theatre in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries: An Expression of the Baroque, Harvard Ukrainian Studies, 1981, vol. 5, pp. 54 ff.

- А. Робинсон. Борьба идей в русской литературе XVII века. Москва 1974.

- See F. Sysyn. Peter Mohyla and the Kiev Academy in Recent Western Works: Divergent Views of Seventeenth-Century Ukrainian Culture, Harvard Ukrainian Studies, 1984, vol. 8, pp. 162-67.

- Z. Kohut. Russian Centralism and Ukrainian Autonomy: Imperial Absorption of the Hetmanate, 1760s–1830s. Cambridge, Mass. 1989.

- Since ideological stereotypes are deeply rooted, it would be useful to think about widening the scope of objective research methods, including statistical ones. Of course, there are many cultural phenomena to which a mathematical approach cannot be applied. On the other hand, existing archives allow quantitative evaluation of the thematic composition of libraries, the character of the book trade, and the religious, ethnic, and regional backgrounds of students, teachers, writers, and artists. It is important to publish catalogues of libraries and the internal documentation of schools and ecclesiastical institutions. Editorial projects that would include all extant sources of this type, not just a selection, are extremely important. One such project is the Harvard Library of Early Ukrainian Literature, which is being published by the Ukrainian Research Institute of Harvard University.