Abstract

This chapter focuses on Kiev during the upheavals of the First World War period by analyzing Czech and Polish ‘spatial stories’ of the city. It examines the effect of the war on the everyday pursuits of pre-war Kievites of Czech and Polish origin and new arrivals to the city. The author ascertains whether and how their perception of Kiev was transformed during the war: from home into lost space. It is argued that Kiev played an important role in the development of the daily activities of Czechs and Poles and that, furthermore, both ethnic groups influenced the city by filling it with their own spatial practices, thereby formulating a unique identity for the city that bore special significance for its migrant communities.

This chapter focuses on Kiev during the upheavals of the First World War period by analyzing Czech and Polish ‘spatial stories’ of the city. It examines the effect of the war on the everyday pursuits of pre-war Kievites of Czech and Polish origin and new arrivals to the city. The author ascertains whether and how their perception of Kiev was transformed during the war: from home into lost space. It is argued that Kiev played an important role in the development of the daily activities of Czechs and Poles and that, furthermore, both ethnic groups influenced the city by filling it with their own spatial practices, thereby formulating a unique identity for the city that bore special significance for its migrant communities.

Вважається, що місто гарніше за село, оскільки воно збагачено людською історією. Правдивість цієї тези можна легко підвередити на прикладі історії Києва. В даній статті увагу зосереджено на міській історії впродовж Першої світової війни та на використанні міського простору чехами і поляками. Використовуючи методологічний інструментарій Мішеля де Серто, зроблено спробу віднайти те мистецтво реакції на виклики повсякдення, яке продемонстрували згадані етнічні спільноти протягом воєнних років. У статті показано послідовність зміни використання міста – від домівки-вітчизни до втраченої території. Це відбувалося крізь призму творення свого власного простору, прочитання міста крізь наділення його об’єктів та простору значеннєвими кодами. Впродовж війни попри те, що чеська і польська спільноти значно збільшили свій кількісний та змінили свій якісний склад, сприйняття міста, його ідентичність не змінилися, однак вони щезли разом із їхніми творцями. У статті простежено просторові історії та виокремлено просторові практики, сповнені особливої пам’яті, що поділялася усіма чехами та поляками Києва. Війна змінила значення деяких об’єктів міста, готелі якого були переоблаштовані під офіси та місця політичних зібрань, публічні приміщення, цирк, стали свідками видатних конгресів, монастирі та університет відкрили свої терени для формування не своїх військових підрозділів (Чеської дружини). Це лише перша спроба прочитати Київ крізь просторові історії його мешканців, прояв спокуси затримати на довше блимання вогника, який у вигляді ностальгійних спогадів дозволяє нам відчути себе в постаті тих, чиї давно зниклі кроки оживляли Київ.

Introduction

You can meet in the streets of Prague a shabbily dressed man who is not even himself aware of his significance in the history of the great new era. He goes modestly on his way, without bothering anyone. Nor is he bothered by journalists asking for an interview. If you asked him his name he would answer you simply and unassumingly: ‘I am Svejk’1.

That is how the prominent Czech writer Jaroslav Hasek pulled an anonymous inhabitant out of the embrace of the street, introduced him and forced us to follow his steps, to read his ‘spatial stories’, during the 500 pages of his book. Reading this novel, one actually does what Michel de Certeau wanted all of us to do– to understand the subject in space while reading his or her own spatial stories. I consider Svejk’s urban experience – ‘the murmuring voice of societies’ – to be a good way of demonstrating de Certeau’s technique, but what can we say about Hasek in this context?

A building on Volodymyrska Street in downtown Kiev bears a plaque with the inscription: “Jaroslav Hasek, a famous Czech writer, lived here during the World War I”. This is the only name that has been commemorated out of almost 50,000 Czech and Slovak people in Ukraine. A large part of this community marched through Kiev in the late winter of 1918 leaving the city for Prague via Vladivostok. However, my task here is not to write a story about Hasek, but rather to produce, or else find, de Certeau’s “science of singularity”2 – a science of the relationship which linked the everyday pursuits of the inhabitants to the particular circumstances of World War I in Kiev. Thus, my intention is to show how culture – “a system of inherited conceptions expressed in symbolic forms by means of which people communicate, perpetuate, and develop their knowledge about and attitudes toward life”3 (Clifford Geertz) – was consumed by ordinary Czech and Polish men far from their homeland, in their new Heimat – a Ukrainian metropolis. This kind of approach helps avoid the pitfalls of nationally oriented studies, which still prevail in Ukrainian, Czech and Polish historiographies. The authors of Capital Cities at War: Paris, London, Berlin 1914-1919 demonstrated that the history of World War I can be better understood if one investigates its events through urban studies, paying attention to the metropolis as the “social formation at the juncture between the national state and civil society, as defined by collectivities of many kinds”4. Following their approach, this chapter will not focus on the urban level of waging war but rather on the urban activities of an under-researched collection of city-dwellers, namely minority ethnic groups. Specifically this study is concerned with the Czech and Polish indigenous population and new arrivals, who together transformed Kiev into an immigrant city by 1917.

The specific questions I will ask below, in terms of the ‘science of singularity’ framework, are: How did the Czechs and Poles perceive Kiev? Where did they concentrate and how did they inhabit the city space? What did their daily routes look like? Where did they start and end? Which places bound these ethnic groups together through common memories? How much did the War influence the usual traditions of city life and reformulate urban identity? In this article I attempt to answer these questions by examining them in terms of the key formula – Ubi bene ibi patria5. Research of this kind can reveal an interesting and rare phenomenon in urban history, when a city’s fate depended not on the indigenous population, but on the newcomers who came to the city as refugees, rather than permanent occupants.

Kiev as Heimat

Polish colonization of Ukrainian territory began several centuries before the start of Czech colonization. The former can be traced back to 1569, when Ukrainian lands became an integral part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The latter was mainly rooted in late 19th century Pan-Slavist sympathies. Nevertheless, one should not forget that the first Czech colonists appeared in Ukraine soon after the defeat of Czech rebels in the battle of Bila hora [White Mountain] in the first half of the 17th century. Despite this, before World War I both ethnic communities6 considered the land where they had settled as their motherland, their home, and a place of safety. They took root in these lands and filled them with their own memories and stories. “We were the citizens of this land, which owes everything to us”, Polish colonists in Ukraine used to say (a statement echoes the discourse of colonialism worldwide)7. The status of Czechs and Slovaks differed slightly; it may be summarized as follows: “in the harsh conditions of the Russian Empire, most of them had lost interest in their native country and its problems, becoming thoroughly Russified”8. The best expression of the migrants’ identification with the Ukrainian lands was conveyed by the name which both the Polish and the Czech communities used to designate Ukraine: they called it Rus’ (referring to the medieval state Kievan Rus’) and its native population, Rusyny (Ruthenians). The Czech colonists probably adopted the name Rus’ from Poles9, who wanted to emphasize their own, rather than Russian, legacy and tradition in these lands10. But the question is how much these attitudes were preserved within the city walls. If Ukrainian lands were perceived as a homeland, what role did Kiev play for these ethnic groups?

There are many starting points from which to answer the questions mentioned above and, in this way, to read the Czech and Polish spatial stories of Kiev. If we give the floor to a flâneur, we can see that the description of a city naturally begins with an edge: “I see my city picturesquely situated on the right bank of the Dnieper… I see this city immersed in the green beauty of the charmed parks that embellish the hills under the river bank…”11. As in this quotation, the Dnieper, which divides Kiev into two parts, was the line from which the Poles and the Czechs customarily drew their map of the city. But the river bank did not expose “an entire metropolis to view”12, as Lake Michigan in Chicago did in Kevin Lynch’s classic example of the edge, without which the city cannot be pictured13. Rather, it marked the developed part of the city and created a beautiful cityscape visible from the non-urbanized opposite bank of the river, where the first recreation districts began to appear at the turn of the 20th century. The river bank also had another function. It was the end of the usual path, which led a flâneur to the main cultural events that took place in the city and were organized in the numerous parks and districts along the Dnieper, for example, in the Kupetski Sady (Merchants’ Gardens) or in the trade area in Podil. One could enjoy concerts, dances, talks, singing, playing cards, and flirting there. It was the most romantic part of Kiev and an area that encouraged a feeling of belonging. This kind of spatial practice neglected all differences between city-dwellers. However, these differences surfaced immediately after leaving this area. They arose when visitors returned along the routes that had led them to the river bank. Thus, at this stage we come to another possible starting point in our attempt to read the urban space, which may be narrated as follows: “Let us take a tour from the edge in summer 1914” or “Were we to follow one of the residents along her typical route to the Dnieper, the experience would be something like this”14.

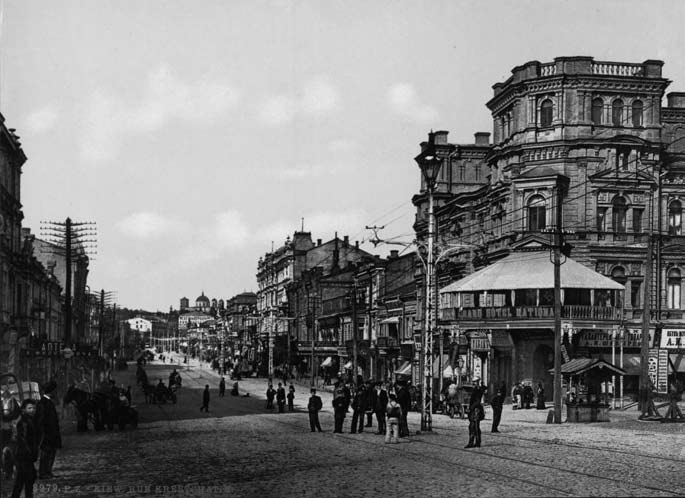

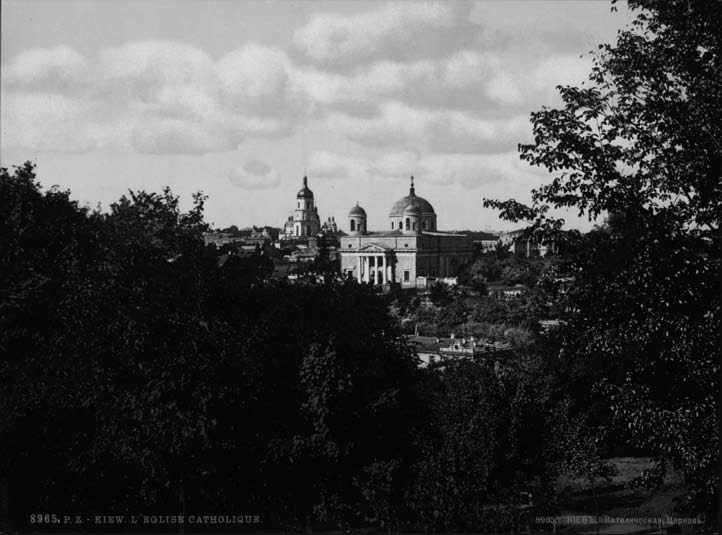

Fig. 1

View at Podil.

The task is not easy, however. Ordinary people of Czech and Polish origin left so little evidence of their city life that one may only guess at how their itineraries were organized. The sources that remain allow us to reflect on how urban space was occupied by communities in general, rather than how they articulated their social differences using the urban landscape. Indeed, in this case Kiev becomes fragmented into different parts, the histories of which can unfold “like stories held in reserve”15. To evoke these stories let us take a closer look at the city in general. By the beginning of World War I Kiev was one of the most pleasant cities in the Russian empire. Under the influence of the new industrial age, the city had expanded rapidly. New multistoried houses with apartments for rent were built everywhere; a regular water supply became standard across the city centre; new roads were paved; electric lights replaced the old gas lights along the streets; and tramlines connected the city centre with outlying areas. All this made Kiev increasingly attractive to businessmen, traders, and craftsmen. Also, by the end of the century it became an important educational centre. These changes caused an increase in the city’s population. Part of this population growth was made up of the two ethnic groups we are interested in. Between 1897 and 1914 the Polish population grew from 35,552 to 60,000 (the total population of the city on the eve of the War was 600,000)16. Kiev also became attractive to the Czechs. In 1909 the young Czech community comprised as many as 3,000-3,500 members17.

The industrial age finally defined the functions of the city districts. ‘Little Paris’, as people sometimes called Kiev at the time, received its newly restored and very wide street, Khreshchatyk, which became the main artery of the city. Its appearance was shaped by numerous hotels, stores, restaurants, cafes, and business offices. At the same time it was also the place for everyday strolling. It was beautiful, and attractive to those who had capital and wanted to start a new business in the city. So, taking into account that the Poles were the richest landlords in this part of the Russian Empire, it is not surprising that there were a large number of Polish landmarks on the Khreshchatyk. On this street one could find Marszak’s jeweler, Fruzinski’s cafes and Idzikowski’s bookstore and library18. The latter was well known in the Russian Empire and in Europe for its rich collection of music literature. In another district one could find the musical instruments store which belonged to local ‘Czech king’, Jindrich Jindrisek. The intellectual district was also nearby, marked by St. Volodymyr University, the Second Gymnasium, the Opera House, and the City Theatre, all of which were located along Volodymyrska Street. Although these were places which let all inhabitants enjoy the same social relations with the city, the paths that led there were quite different. On the way to the Opera House Polish inhabitants could stop by Franciszek Golabek’s amazing Hotel Francois, which featured a nice restaurant with tasty deserts and famous poolrooms. In contrast, the Czech path to the opera went via the Praha hotel, which is the most famous hotel along the street. It belonged to Dr Vaclav Vondrak, one of the richest Volhynian Czechs and a deputy to the Volhynian local self-government body, the zemstvo. The hotel’s advertisements claimed: “You have not been to Kiev if you have not seen the city from the hotel’s roof ”. The hotel was the main landmark for Czechs in Kiev.

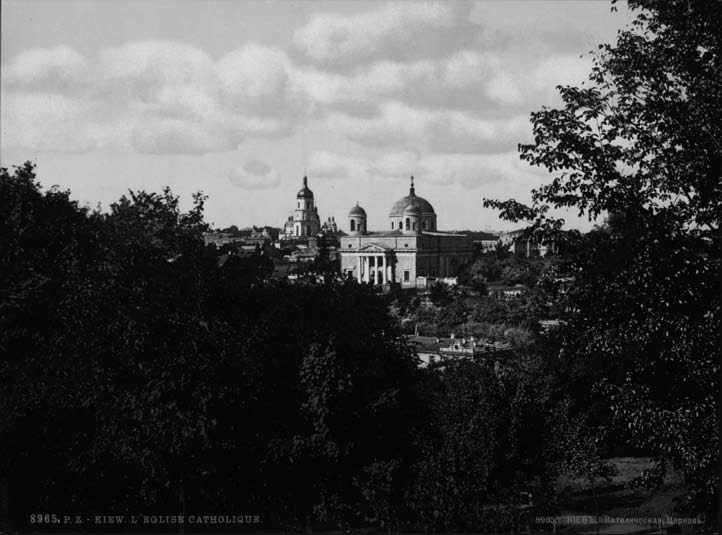

Fig. 2

Khreshchatyk.

Fig. 3

View at St. Volodymyr University.

Fig. 4

St. Volodymyr holding a cross.

If one continued the tour all the way to the beginning of the street, one would reach Podil, the oldest trading region, passing St. Volodymyr’s hill, on top of which a figure of St. Volodymyr holding a cross was erected in 1853. This was the district most closely connected with the Poles. Normally Podil, as is typical for trading areas, had a “multiplicity of contact points”(Sennett) between ethnic groups, but once a year the area was immersed in Polish subculture. Each February many Poles from Kiev and other regions of Ukraine left their homes or homesteads to participate in the most important annual Polish event in Kiev – the Kontraktovyi Yarmarok (Contract Fair). Participation in the event could lead to a successful business deal, a good marriage proposal or a nice job offer, and guaranteed general revelry in the carnival atmosphere of non-stop balls, cards, etc. The Poles penetrated into all parts of Kiev during the fair. Hotels were overcrowded and all nearby apartments were rented19. The event helped unite the Polish community by bringing together Kievites of Polish origin and the Poles who lived in the provinces.

In contrast to the Poles, the Czech ethnic group in the city did not have any event which knitted their social lives together. However, there was an entire district in one of Kiev’s suburbs which belonged to them. Officially, its name was Shulavka, but for the Czech inhabitants it was known as Ceska Stromovka. The origins of the district are associated with the Prague born engineer Josef Krivanek, who came to Kiev as a technical assistant from the Czech plant “Broumovsky a Sulc” in the early 1880s and, by 1888, became the director of Grether’s plant located in Shulavka. Within ten years, the plant, which was known as the “Kiev Grether-Krivanek Machine Works and Boiler Plant” became one of the most advanced and productive machine works in Ukraine. At the end of the 1880s, another Czech, Mr. Vesky, founded another factory – “Vielwerth a Dedina” – which became the largest producer of seeding machines in the region20. A lack of local engineers, qualified clerks and builders caused the owners to employ specialists from the Czech lands. Some of them became managers in the plants, some were workers, but regardless of their positions almost all of them dwelled in Shulavka. However, one has to remember in this context that there was another source of the growth of the Czech community in Kiev. The city became attractive to the first generation of Volhynian Czechs, who found better career opportunities in the metropolis at the beginning of the 20th century. Also, some Czechs moved to Kiev directly from Austro-Hungary for ideological reasons. These new arrivals lived in different parts of the city and some of their apartments soon became the centres of Czech intellectual life in Kiev.

What is of most interest to us is how the Poles and the Czechs constructed their urban communities through their own communication infrastructure in Kiev, or, in other words, how they inhabited the city through their own texts. On 1 February 1906 Wlodzimierz Grocholski, the Vice President of the Kiev Agricultural Society, published the first edition of “Dziennik Kijowski” [Kiev Daily], which became the main media outlet of the Polish community in the city. Its motto was “the responsibility of each Pole is to care for Polish prosperity”21 and its political priorities were close to the national democratic ones22. This periodical and the different Polish organizations, clubs, and charity societies, where the Poles regularly met, created a recognizable Polish culture in Kiev. It helped the Poles express their claim to the urban space of Kiev and use it to stage Polish cultural events. It also helped the Poles to read Kiev in the same way. The Czechs carried out similar practices in the city. On 17 October 1906 the first issue of the Czech newspaper “The Russian Czech” was published in Kiev by Dr. Vaclav Vondrak. Even though only a few issues were published, the role it played in Czech life was very significant. It united the Czechs and inspired them to establish closer connections through the newly founded organizations23. The most successful Czech project in Kiev, however, was “Cechoslovan” – the official Czech and Slovak newspaper in the Russian Empire. It was published by Venceslav Svihovsky with the financial support of

Czech businessmen.

The significance of these periodicals was remarkable. Both of them stressed the identity of Kiev for their readers, showing them clear signifiers of the city’s borders, landmarks, and the paths which connected them and structured city life. Through brief announcements, advertisements, and news the periodicals told their readers where to shop and what to visit.

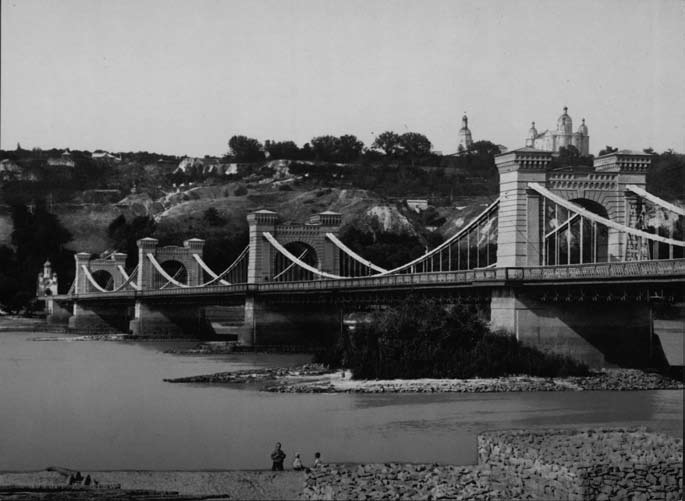

Fig. 5

St. Alexander’s Cathedral.

They helped the inhabitants make their own daily journeys, penetrating into different districts, passing by different landmarks, becoming flaneurs for a while, with the purpose of reaching places which bore significance for their ethnic groups. There were very few places that were identified with only one community. However, the main landmarks for the Poles were the two Catholic cathedrals (the old one – St. Alexander’s Cathedral – in downtown Kiev, and the new one – the neo-gothic St. Nicholas’ Cathedral – several miles away from the centre). The Jan Amos Komensky Charity Educational Society in Kiev located in J. Jindrisek’s store in Khreshchatyk played the same role for the Czechs.

To sum up, by the beginning of World War I the Czech and Polish communities had very clear images of the metropolis. Both of them had their own infrastructure of communication, which included newspapers, stores, hotels, schools, industrial plants, and in this way they inhabited the space with their own spatial stories. As in other cities of the Russian Empire24, this infrastructure was established by public figures, landlords, and factory owners. In so doing they organized the ordinary Czechs and Poles into new local communities in Kiev and helped them perceive Kiev as their Heimat.

Kiev as a rented apartment

The beginning of World War I was a turning point in the lives of the Czechs and Poles in the Russian Empire. The war became the dominant influence on the population. It was everywhere, involving each family and entering everyone’s life through news and, above all, via the declarations and orders issued by the new authorities. This was a moment when all non-Russian ethnic groups were reminded by officials of their origin and citizenship regardless of their loyalty towards the empire. Those who did not apply for Russian citizenship were regarded as enemies and the government ordered them to be arrested or moved to special places under police control. There were a lot of absurd situations, mostly in Czech families, in which a husband joined the Russian army as a Russian citizen and his wife, still having Austrian citizenship, was forced to leave their home25. The problem of ethnicity shaped the new perception of the city dwellers. It distinguished and named outsiders. In Kiev the group that stood out was, above all, the Czech community because their native land was part of an enemy power – the Austro-Hungarian monarchy – and supplied soldiers to the army against which native Kievites had to fight. Similar situations occurred in Paris or in London, where a German waiter would suddenly become an outsider, or in Berlin, where the same would happen to British students26.

In order to avoid mass resettlement and arrests, the Czechs had to demonstrate their loyalty to the Russian Empire. This was the first time that the Czechs were forced to change their perception of the city space because of an external influence. On 27 July 1914 they organized a meeting in downtown Kiev using the open space for their activities. Speeches were addressed to the authorities and proclaimed the willingness of the entire Czech community to apply for the Russian citizenship, as well as to establish an independent Czech state under the protection of Russia27. Furthermore, the government ordered the creation of a Czech unit in the Russian army on 30 July. It was called Druzhina and located in Kiev under the control of the Kiev headquarters28. The unit’s flag was blessed by the clergy during a solemn meeting on Sofiivska square in Kiev on 28 September in front of the 11th-century orthodox St. Sofia’s Cathedral and the monument to Bohdan Khmelnytsky, a Ukrainian hetman. Since the Middle Ages the square had been the usual place for holding great events. Thus, the meeting was not a unique or unusual use of the urban space. However, the spirit with which the Czech community used it was the first signifier of the wartime influence on the city life, when the decisive features of urban rhythms and customs were “a function of the decisions taken elsewhere”29.

Fig. 6

St. Sofia’s Cathedral.

Fig. 7

St. Michael’s Monastery.

While the square became recognized as the birthplace of the Czech Druzhina, the other sacred place for Orthodox Christians – St. Michael’s Monastery, located one mile away – opened its gates to the first volunteers to join the military unit30. Soon enough the Czech volunteers were joined by Czech and Slovak prisoners of war and deserters from the Austrian army. They were transported from the front line to Kiev where they faced a difficult life.

These new arrivals reformulated urban identity. They designated new landmarks, drew new edges, and imbued new routes through the city with meaning. The Czech and Slovak captives were concentrated in the Darnytsia camp located in a suburb on the opposite side of the Dnieper. Thus, the significance of the river changed for the city’s inhabitants. It no longer linked the urbanized and highly industrialized area with the undeveloped but beautiful and romantic landscape. The river became a dividing line between the spatial practices used by completely different worlds, those of the prisoners of war and the city’s inhabitants, rather than the connection of different practices of the same world. Moving along the bridge from the right to the left bank of the Dnieper, the deserters left normal city life, still brimming with the usual daily activities of its inhabitants, and met the challenges of the war period in poorly made barracks where they lived the stressful lives of captives.

The appearance of these newcomers in Kiev forced the local Czech community to change its role. Meetings with civilian and military authorities, in order to negotiate the deserters’ destiny in Kiev, became one of the main activities of its leaders. These meetings were part of V. Vondrak’s and J. Jindrisek’s daily responsibilities as they tried to get the authorities to permit the captives to be drafted into the Druzhina31.

The war also changed the infrastructure of communication. The Praha Hotel became the focal point of the Czech community in the city. A network of Czech organizations was also established in the Russian Empire. In August 1914 the Union of Czech Societies in Russia was founded on the initiative of the Komensky Charity Foundation; its first meeting was held in Moscow in 1915. Kiev was represented in this Union by the newly established Czech Committee for supporting war victims headed by Jiri Jindrisek. It was located on 43 Volodymyrska Street. The committee was responsible for providing former Austrian citizens with documents which confirmed their Slavic origin and allowed them to live in the Empire32. Thus, most of the events which occurred within the Czech community during the War period took place on Volodymyrska Street. However, this does not mean that other ethnic groups perceived the street and nearby area to be a special Czech district. The Czech spirit was to a large extent concealed within the buildings that lined the street, for example, in the Praha Hotel or in the buildings of St. Michael’s Monastery, which functioned as a base for military formations.

Whereas the spatial practices of the indigenous Czech community in Kiev were influenced by two categories of countrymen, i.e., the former Austrian subjects (‘war victims’) refugees was actually “resettlers”: “The mandatory evacuation organized by the authorities forced us to leave Sarny. So in September we found ourselves in the Italia Hotel on Prorizna street in Kiev”34.

One cannot say how many Poles found themselves in the Ukrainian metropolis during the War. However, it is obvious that Kiev became the only city in the Empire where the Polish community not only maintained its activities but also developed them. According to memoirs the city came to be dominated by Polish culture35. It resembled February in pre-war Kiev, when Poles arrived to attend the Contract Fair. It could be also been described as a “rented apartment” (de Certeau). However, this time the opportunities were quite different from those which were offered by the Contracts Fair. Nobody could estimate for how long the city space would be borrowed by the new Polish transients. Many unknowns dictated new rules of urban usage. The growth of the Polish population resulted in the establishment of private and secondary schools, initiated by the clergy of St. Alexander’s Cathedral36. Moreover, the refugees brought with them their newspapers, weekly periodicals, and other signifiers of their previous city life in Warsaw or in Galician towns, using which they started to influence life in Kiev. Finally, the Polish theatre was founded in Kiev in 1916. It united the Polish community within its walls, becoming a new element in the city’s communication infrastructure37.

Similar changes occurred within the Czech community in Kiev in 1916. The influence of newcomers, such as the captives, on Czech urban rhythms significantly increased. There was no part of Czech life in the city which was not transformed by their arrival. They became city dwellers and, what is more, involved the pre-war Czech community in the creation of an entirely new project – an independent Czech state. They became members of the Club of Captive Co-Workers founded in 1916 and affiliated with the Union of Czechoslovak Societies in Rus’. The club represented the interests of its members, and provided housing and food38. Furthermore, newcomers became members of the Czechoslovak Credit Society, which also opened on Khreshchatyk in 191639. They went back and forth between the campus of St. Volodymyr University, where their new military units were trained, and their camp in Darnytsia. Not only did they settle the city, but they also articulated their existence there:

Dear professor, the historical commission under your presidency organizes lectures for pupils in the secondary schools in Kiev. These lectures aim at the development of better understanding of current events by way of learning the history of friendly states. With this in mind, we would like to ask you to include a lecture about the history of the Czechoslovak people since the 16th century into the lecture cycle as well. We ask Pavlo Rodionovich Timoshok to deliver this lecture40.

This letter was sent by the members of the Club, i.e., by former captives who later became responsible for the further development of the Czechoslovak military unit and the Czechoslovak life in Kiev. Their usual tactic was to find ‘friends of the Czechoslovak people’ who could help them either with disseminating information about their movement or with better contacts with the authorities:

Dear Konstantin Pavlovich Belkovskii, we regard it as our duty to thank you for your efforts aimed at informing the readers of newspaper “Kievlanin” about our people. Your articles demonstrated your deep knowledge of the subject, but if necessary, we are ready to provide you with further information”41.

This letter was sent by Vladimir Chalupa, the head of the Club and a former deserter. Despite all the changes within the Czech and Polish communities mentioned above, their perception of Kiev was not radically altered during the first years of the War. Rather, it was supplemented by the new “underlying city form elements” (Kevin Lynch), such as a camp for captives in Darnytsia or the Polish theatre in downtown Kiev. At the same time, the significance of older landmarks for the private life of the ethnic groups only deepened. None of these changes transformed the Czech or Polish image of the city. Nevertheless, it was not the same city as it had been in June 1914. It was not a Heimat anymore. The uncertainties of wartime and the arrival of the new immigrants changed the attitude of the Czechs and Poles to the city. They began to believe that their well-being in Kiev was temporary. They began to lose their perception of themselves as natives of Kiev and instead began to see themselves as tenants or renters of the city space.

Kiev as a lost city

If one wants to study how a city loses its identity, one could not find a better example, than Kiev in 1917-1918. First, the city changed its status, becoming the capital city of the Ukrainian state in January 1918 and, by virtue of this, developing new spatial practices. Secondly, the city was occupied by a foreign power and became involved in civil war and revolution. Finally, it lost its population whose actions had given the city its character and identity.

The first hints of the future catastrophe appeared at the beginning of 1917, when the February Revolution drastically altered life in the entire Russian Empire. The meaning of the event for Kiev was later depicted by Mikhail Bulgakov as follows:

But these were legendary times, times when a young, carefree generation lived in the gardens of the most beautiful city in our country. In their hearts they believed that all of life would pass in white light, quiet and peaceful, sunrises, sunsets, the Dnieper, the Khreshchatyk, sunny streets in summer, and in winter snow that was not cold or cruel, but thick and caressing... But things turned out quite differently. The legendary times were cut short and history began thunderously, abruptly. I can point out the exact moment it appeared – it was at 10:00 a.m. on March 2, 1917, when a telegram arrived in Kiev signed with two mysterious words, ‘Deputy Bublikov’42.

This indicated a change of authority in the Empire.

There is no evidence that the change of regime influenced the spatial stories of the Czechs and Poles in Kiev. The transformation did not lead them to change their perception of the city, rather it was a signal prompting them to proclaim new goals and tasks which would lead to the independence of their own states. Kiev was uniquely well suited to the pursuit of these aims, as it was located far enough from the centres of the revolution to allow a degree of freedom and normality in the city. That is why the political activities of both ethnic groups came to be based in Kiev43. The newly founded Polish executive committee in Rus’ (Polski Komitet Wykonawczy na Rusi) and the Section of the Czechoslovak National Council in Russia (Odbocka Cesko-Slovenske Narodni Rady v Rusku, or OCSNR) became the main representative organs of the respective ethnic communities in Kiev.

Despite the eventful beginning to the year, in November 1917 Kiev’s inhabitants continued their usual spatial practices throughout the city. However, the legendary shot fired by the cruiser Aurora, which signalled the beginning of the Bolshevik revolt in Petrograd on 25 October (7 November) 1917, annihilated all existing spatial practices.

The October Revolution directly affected Kiev. Newspapers wrote that the city, which had avoided the brunt of the war, faced the threat of domestic upheavals. In early November 1917 the first armed conflicts took place between the military units of the Provisional Government and the Bolsheviks in Kiev. Some Czechoslovak units were involved in the conflict. Being under the control of the Russian army headquarters (Stavka), they could not remain neutral when they received an order to help the Stavka in the clash in the Mariinski Park. The Czechoslovak leaders did not have any influence on them. They did not even know exactly what the status quo was. For example, they knew that the two Czechoslovak companies found themselves in the centre of the conflict on Mariinski Park. However, they did not know against whom those companies fought – the Bolsheviks or Ukrainians44. To avoid further involvement of Czechoslovak soldiers in domestic conflicts in Kiev, the Presidium of the OCSNR proclaimed strong neutrality with respect to the political situation in the former Russian Empire. They agreed to remain observers of the events in the city, rather than participants. This neutrality, however, led to their transformation into city guards later on45.

Unlike the Czechs, the Polish ethnic group changed neither their perception of the city nor the role they played in the city life. They participated in all meetings organized by the Ukrainian authorities and had representatives in the newly established Ukrainian government. However, they could not continue their previous activities at the same rate. Life during a time of conflict dictated its own set of rules.

This became evident when Tomas Masaryk came to Kiev, fleeing from Moscow which had fallen to the revolutionaries. In order to read Kiev through Czech spatial stories at that time, we should follow Masaryk’s footsteps. He was neither an inhabitant, nor a refugee. Masaryk was a guest in the city, who visited his countrymen for his own political purposes. As a guest he became acquainted with all the places significant for the Czech community. He did not visit the Praha Hotel, probably because Dr Vondrak had lost his influence in the Czech community in April 1917 and did not support Masaryk’s policies. He did, however, go to the Hotel de France in Khreshchatyk and Ottokar Cerveny’s family apartment, which became a second home for many Czechs. He visited the Ukrainian authorities and established connections with the Polish community in Kiev. The results of his movement through the city were the relocation of the OCSNR regular meetings, which were then often organized in Cerveny’s apartment, and that some places came to have meaning for both Czechs and Poles. As a result of his activities an anti-Habsburg movement was established, based in a circus in Kiev. A meeting of the suppressed and divided peoples of Austro-Hungary, organized in cooperation with Polish leaders, took place there on 12 December 1917 and was attended by 4,000 participants46. It was that “contact point” (Sennett) that allowed both ethnic groups to enter into the same relationship with the city.

At the same time Masaryk became a key figure and had a great influence on the future of the city. In early February 1918 Kiev was occupied by the Bolsheviks. Only 300 young Kiev students tried to stop the Bolsheviks’ offensive and were killed near Kruty on 30 January 1918, not far from the Ukrainian capital. Ukrainian politicians sent delegates to Tomas Masaryk and tried to use the well-disciplined Czechoslovak military units in the struggle against Bolsheviks. However, Masaryk insisted on their neutrality and did not permit the involvement of the Czechs and Slovaks in “domestic Russian affairs”47. Thus, the Czechs did not play the role of Roman geese. They did not attempt to save the city but it seems unlikely that they would have succeeded had they done so. The Bolshevik occupation of Kiev meant that the Czechs lost access to the city. This became evident when the Czech soldiers were forbidden to visit Kiev by the OCSNR. The reason was explained as follows: “They (Kievities) do not like us and there were occasions when our riflemen were beaten”. Those Czechs who remained in Kiev, in turn, said: “I command all Czechoslovakian troops who are at the moment located in Kiev City to refrain from walking on the streets. Only in the case of necessity should individuals be sent on official assignments”48. Within less than a month the Ukrainian authorities came back to Kiev, but with its new allies – the German and Austro-Hungarian forces.

The Czechoslovak legion and Czech political leaders left Kiev for Vladivostok at the beginning of March. The Czechs and Slovaks who remained in the city, mostly pre-war inhabitants but also former captives who did not share Masaryk’s vision, again became outsiders in the city. This time they were accused of being enemies of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. They had to keep silent and not to show any signs of their existence in the city until the end of the war. In contrast, there was no mass exodus of Poles from the city nor did they change their routes within the city space. However, they partly reoriented their activities towards Warsaw, now that they were able to return there, and towards its main representative – the Regency Council, a creature of Germany. This was the fourth upheaval which Kiev was to face in this short period. Bulgakov wrote:

In that winter of 1918 the City lived a strange unnatural life which is unlikely ever to be repeated in the 20th century. Behind the stone walls every apartment was overfilled. Their normal inhabitants constantly squeezed themselves into less and less space, willy-nilly making way for new refugees crowding into the City, all of whom arrived across the arrow-like bridge from the direction of that enigmatic other city…49.

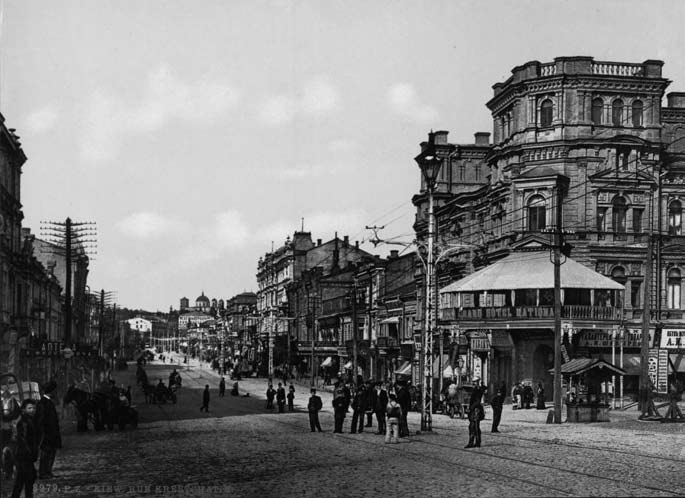

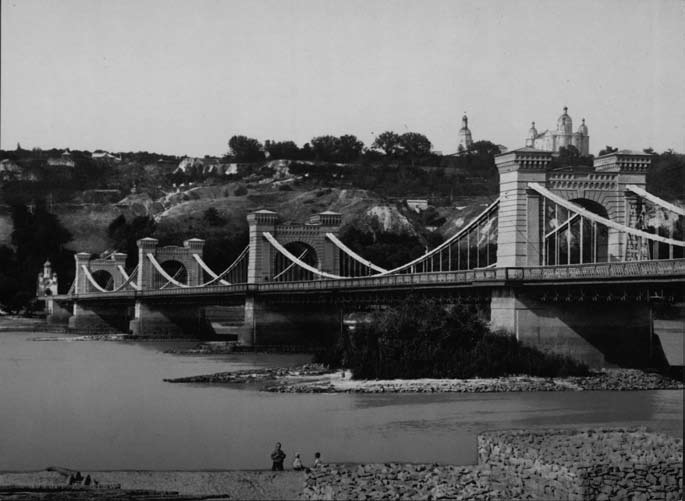

Fig. 8

View of the bridge.

The city faced ten more upheavals. After the last one, in 1920, it was the Poles’ turn to leave Kiev for good. Despite the fact that they left Kiev at different times and under different circumstances, the departure of the Polish and Czech communities transformed the image of the city for good: “Gone with the wind! Kiev stopped being a flourishing, happy, and smiling city, as I remember it from my youth. People, these wonderful Poles with strong necks and wide gestures, that set the pace in the city, were killed or died”50.

Conclusion

There is a saying: “A city is more beautiful than a village, because it is rich with people’s history”. Kiev is a good illustration of this statement. Just like other cities, it was inhabited with the spatial stories of its occupants. Although wartime had a significant influence on the life of Kiev’s inhabitants, the city continued to model and construct their urban life. It consisted of different elements which made the activities of the Polish and Czech communities possible. They lived their lives through familiar paths, landmarks, and edges which were established in the pre-war period. The Polish and Czech newcomers did not reformulate the local urban identity that they encountered upon their arrival. They only enriched it with new recognizable signs and meanings. The unusual circumstances of war led to old places being used in new ways. The hotels were used for everyday negotiations and offices of new organizations, the circus was turned into a hall for huge meetings, and the university and the cathedrals became the base for military units or newly founded schools.

This chapter is the first attempt to read Kiev through the ‘spatial stories’ of the Czech and Polish communities in the city. I am aware that important questions, such as how the urban landscape was used by different social groups within these communities, whether use of the landscape unified or divided them and how the social hierarchy of these communities operated within the city, have not been elaborated in the text. Examination of these aspects, however, needs further research and, thus, will be the subject of future publications on the issue. According to the material analyzed in this chapter one can perceive a change in the Czech and Polish relationship with the city. Before the war they identified closely with the city rooting their lives there. During and after the conflict they began to perceive the city as a rented space and thought of returning to their native lands. Finally, after the revolution, they were forced to leave. If we follow the spatial stories of the Czechs and Poles, we can read Kiev as a unique city filled with elusive, but beautiful spatial practices which tied fond memories to the urban space. Although the city’s diverse identity was lost, enough evidence remains to remind us of the footsteps of Czechs and Poles on Kiev’s streets:

I would like to remind you that Kiev, thanks to its unique inhabitants, differs very much from other Russian cities… It is like a bridge between the European West and real Russia. Different nationalities, Ukrainians, Russians, Poles, Jews, Germans, Czechs and others, meeting on that bridge, created a mixture there… Different national interests of the inhabitants defined Kiev’s image and gave it the character of an international city in which everybody found what they needed and what they liked… I came to Kiev only in 1909 as a Volhynian Czech who had heard about Kiev ten years earlier, and I was filled with endless respect for the metropolis of our South-Western country!51.

Уперше опубліковано: Frontiers and Identities: Cities in Regions and Nations / Ed. By Lud`a Klusakova and Laure Teulieres. Pisa, 2008.

Notes

- J. Hašek, Osudy dobrého vojáka Švejka [The Good Soldier Švejk], Bratislava 2000 [first published 1921-1923], p. 5.

- M. de Certeau, L’invention du quotidien, Paris 1974 [cited from The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Rendall S., Berkeley - Los Angeles 2002 , p. 9].

- Quotation from A. Wierzbicka, Understanding Cultures through Their Key Words: English, Polish, German, and Japanese, New York - Oxford 1997, p. 21.

- J. Winter, J-L. Robert, Conclusion: towards a social history of capital cities at war, in J. Winter, J-L. Robert (eds.), Capital Cities at War: Paris, London, Berlin 1914-1919, Cambridge 1997, p.549.

- Where you feel good, there is your home (Lat.)

- Here, the term “ethnic communities” is defined according to A. Smith and means a social network or series of networks formed by people who possessed specific cultural attributes (common name, history, culture, language, customs, traditions, religion etc.). By the end of the war the Czech and Polish groups start behaving more like national minorities, meeting one of the characteristics of a national minority suggested by Brubaker: “the demand for state recognition of this distinct ethnocultural nationality”. Deeper investigation of how the Poles and Czechs in the Ukrainian lands were transformed from ethnic members into legal citizens of their future independent states is not the aim of this chapter. The issue will be elaborated in the further research. See A. Smith, The Origins of Nations, in G. Eley, L. Suny, Becoming a Naitonal: A Reader, New York - Oxford 1996, pp. 109-110; R. Brubaker, Nationalism Reframed. Nationhood and the National Question in the New Europe, Cambridge 1996, p. 60.

- Д. Бовуа, Битва за землю в Україні 1863-1914. Поляки в соціо-етнічних конфліктах [La Bataille de la Terre en Ukraine 1863-1914. Les Polonais et les conflits socio-ethniques], trans. Z. Boryssiouk, “Критика”, 1998, p. 263. This and other quotations from the Ukrainian, Russian, Polish and Czech original texts are translated by the author of the chapter.

- J.F.N. Bradley, The Czechoslovak Legion in Russia, 1914-1920, New York 1991, p. 14.

- Masaryk, the first president of the Czechoslovak Republic, would later use the name Malorossia (Little Russia), adopting the Russian scheme, or Ukraine, depending on the political situation.

- It is necessary to emphasize here that the words Poles and Czechs used for the territory they inhabited were quite unique to each group and, obviously, contrasted with official Russian imperial discourse. More widely used names for the Ukraine within the empire at that time were Малороссия (Malorossia, Little Russia) or Юго-Западный край (Yugo-Zapadnyi krai, South-Western Land); both names defined the region as an integral part of the Russian Empire. Concurrently, the name Ukraine began to be used in political vocabulary. Andreas Kappeler commented that “only during the second half of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century did the terms ‘Ukraine’ and ‘Ukrainians’, which had been used since the middle ages for particular regions, gradually become the common self-designation of the emerging nation. ‘Ukraine’ has served as the official name of the region only since 1917”, A. Kappeler, ‘Great Russians’ and ‘Little Russians’: Russian-Ukrainian Relations and Perceptions on Historical Perspective, in The Donald W. Treadgold Papers in Russian, “East European, and Central Asian Studies”, October 2003, No. 39, p. 14. See also Nazwa geograficzna. Rozpatrywany obszar [Geographic name. Defined region], in Pamiętnik Kijowski,1959, vol. I, p. 9; М. Грушевський, Хто такі українці і чого вони хочуть [Who the Ukrainians are and what they want], in Політологія: кінець ХІХ – перша половина ХХ ст. Хрестоматія, Lviv 1996, p. 180-181.

- X. Glinka, W cieniu Złotej bramy [In a shadow of the Golden Gates], in Pamiętnik Kijowski, vol. I, 1959, p. 221.

- But it has this function in modern Kiev.

- See K. Lynch, The Image of the City, New York 1960, p. 66.

- Here I follow R. Sennet’s introduction to an imagined tour down Halstead street in Chicago around 1910. See R. Sennett, The Uses of Disorder: Personal Identity and City Life, New York 1971, p. 53.

- De Certeau, The Practice cit., p. 108.

- S. Nicieja, ‘Polski Kijów’ i jego zagłada w latach 1918-1920 w świetle wspomnień kijowian [‘Polish Kiev’ and its death], in “Przegląd Wschodni”, 1992/1993, vol. II, 4 (8), p. 852.

- V. Švihovský Kijev a kijevští Češi [Kiev and Kievan Czechs], in Naše zahraničí. Sborník Národní rady československé, 1923, vol. IV, No. 4, p. 157.

- S. Nicieja, ‘Polski Kijów’ cit., p. 853; X. Glinka, W cieniu Złotej bramy [In a shadow of the Golden Gates], in Pamiętnik Kijowski, vol. I, pp. 223,234.

- X. Glinka, W cieniu cit., pp. 232-235; Ернст Ф. Контракти та Контрактовий будинок у Києві, 1798-1923, [Contracts and Contract House in Kiev, 1798-1923], Kiev 1923.

- Švihovský, Kijev a kijevští Češi cit., p. 157.

- Quotation from Nicieja, ‘Polski Kijów’ cit., p. 854.

- It is common knowledge that national democrats were the most powerful group within the Polish community across Ukraine, as well as in Polish student body at the St. Volodymyr University in Kiev in which young people founded the secret organization Polonia in 1901. Education was another sphere to which Polish public figures paid a lot of attention. In 1904 the society Oświata Narodowa na Rusi [National Education in Rus’] was established by Polish businessmen.

- Z.Rejman, Dr. Vondrák pokrokovec – nebo reakcionář? in “Přiloha ‘Věstníku Ústředního Sdružení Čechů a Slováků z Ruska”, 1930, vol. X, No. 5, p. 2; F. Kovářik, Dr. Václav Vondrák padesátníkem, ibid., p. 3.

- See the pioneering work on the issue: B. Pietrow-Ennker, G. Ulianova (eds.) Civic Identity and the Public Sphere in Late Imperial Russia, Moscow 2007.

- J. Vaculík, Dějiny volyňských Čechů [The History of the Volhynian Czechs], Prague 1998, vol. II, p. 6.

- Winter, Paris, London, Berlin 1914-19 cit., pp. 14-15.

- Archív Ministerstva Zahraničních Věci (AMZV), SA, Spolky 5, Český komitet v Moskvě, Телеграмма. Петроград 13 Богумилу Чермаку спр. В., Знаменская 19 [Archives of Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Prague, Siberian Archive, Associations, box 5, the Czech Committee in Moscow, Telegram, Petrograd 13 to Bohumil Čermák spr. V., Znamenskaia 19].

- В. Драгомирецкий, Чехословаки в России 1914-1920 [Czechoslovaks in Russia 1914-1920], Paris - Prague 1928, p. 14; Б. Татаров-Альберт, Драматичні сторінки історії [Dramatic Pages of History], in “Хроніка 2000: Чехія” [Chronicle 2000: Bohemia], Kiev 1999, vol. 29-30, t. II, p. 272-274.

- Winter, Paris, London, Berlin 1914-1919 cit., p. 23.

- The Druzhina consisted of four companies. There were 1,012 soldiers in the unit at the beginning of October 777 of whom were of Czech origin. See F. Šteidler, Československé zahraniční vojsko [Czechoslovak army abroad], in Československá vlastivěda. Stát, Prague 1931, vol. V, p. 558; В. Драгомирецкий, Чехословаки cit., p. 18;

- See Н. Ходорович, Пламенный патриот (Из воспоминаний о д-ре В. Вондраке) in “Přiloha ‘Věstníku Ústředního Sdružení Čechů a Slováků z Ruska”, 1930, 10, 5, p. 5.

- AMZV, SA. Spolky [Associations], box 13, book 2, p. 13, 17.

- See M. Mądzik, Z działalności Kijowskiej Rady Okręgowej Polskich Towarzystw Pomocy Ofiarom wojny w latach I wojny światowej [On the activities of the Regional Kiev Council of the Polish Society for Supporting war Victims during World War I], in Pamiętnik Kijowski, vol. VI, ‘Polacy w Kijowie’, Kiev 2002, pp. 184-185.

- S. Walewski, C.K.O. w Winnicy na Podolu [C.K.O. in Vinnytsia in Podole], in London 1966, vol. III, p. 149.

- See W. Gunther, Polski teatr w Kijowie [Polish theater in Kiev] in London 1966, vol. III, p. 194.

- The Russian authorities issued the appropriate permission in October 1915. Statistical data shows that pupils mostly consisted of newcomers, e.g. there were 79 children from Congress Poland among 150 pupils in a school founded by St. Alexander’s Cathedral. See S. Sopicki, Omówienie pracy Jana Korneckiego ‘Oświata Polska na Rusi w czasie wielkiej wojny światowej’ [The discussion on Jan Kornecki’s book “Polish education in Rus’ during World War I”], in Pamiętnik Kijowski, 1959, vol. I, p. 199.

- At the same time Kiev became attractive to conspirators who established their own ‘subculture’ and had a completely different image of the city. A conspiracy network was initiated by the Polish Socialist party members in general and by Józef Piłsudski, the future head of the Polish state, in particular. Their goal was the establishment of an independent Polish Republic. In January 1915 a conspiratorial Polish military organization (POW – Polska organizacja wojskowa) opened a branch in Kiev. It depended on the Zhytomyr unit and was led by Józef Bromirski. By 1917 all the units of the organization in Ukraine were controlled by Kiev, which turned the city into a center of the Polish insurgent movement against the Russian empire. See M. Wrzosek, Polski czyn zbrojny podczas Pierwszej wojny światowej: 1914-1918 [The Polish millitary action during the World War I: 1914-1918], Warsaw 1990, p. 377.

- AMZV, SA, Spolky, box 11, Stanovy spolupracovníků Svazu Česko-Slovenských spolků na Rusi. Kopie. Schváleno Svazem na schůzi [Statutes of the Club of Captive Co-Workers affiliated with the Union of Czechoslovak Societies in Rus’. Copy. Declared at the Union meeting on 26/Х 1916, N. 726, 28/X 1916].

- V. Ambrož, Češi a Slováci v Rusku [Czechs and Slovaks in Russia], in Naše zahraničí. Sborník Národní rady československé, 1922, vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 97-100.

- AMZV, SA, Spolky, box 11, Его превосходительству Павлу Николаевичу Ардашеву, профессору университета св. Владимира, председателю Исторической комиссии при Киевской учебном округе, Kiev, undated.

- AMZV, SA, Spolky, box 11, Dopis K. Belkovskému. Odesláno 24.11.1916 [Letter to K. Belkovskii. Sent on 24 November 1916].

- M. Bulgakov, The City of Kiev, in Id., Notes on the Cuff and Other Stories, Ann Arbor 1991, p. 207.

- On 2-3 March, the first congress of Polish political parties was organized in Kiev. According to its decision the “committee of nine” was established. The committee was responsible for organization of Polish representation in Rus’. The delegates from more than 30 polish organizations located in Ukraine participated in its first meeting on 6 March in Kiev. The Polish executive committee in Rus’ (Polski Komitet Wykonawczy, or PKW) was established by them. On 7 March J. Bartoszewicz, former editor of Dziennik Kijowski, was elected as its chair. Within the next three months 127 Polish Societies applied for participation in the Committee activities. See: Archiwum Akt Nowych w Warszawie (AAN), Organizacje polskie w Rosji, sygn. 37, p. 24; H. Jabłoński, Polska autonomia narodowa na Ukrainie 1917-1918 [Polish national autonomy in Ukraine 1917-1918], Warsaw 1948, p. 36. At the same time in April Kiev became a host city for the 3rd congress of Union of the Czech and Slovak Societies in Russia. It was not only the most fruitful congress, but also the last one. 48 organizations and societies from the whole Russian Empire participated at the congress, among them: the Czech Committee for war victims support of J. Jindřišek, Jan Amos Komenský Society, Voluntary Fire Units in Kvasyliv, Semyduby; the Czech Committee in Sumy; Society of Russsian-Czech-Slovak economic cooperation in Kiev, the Czechoslovakian Society in Berdychiv (factory ‘Progress’); the Czechoslovak Credit Society; the Czech Society in Poltava etc: AMZV, Spolky, box. 13, České spolky zastoupení ve Svazu česko-slovenských spolků na Rusi [Czech association represented in the Union of Czecho-Slovak associations in Russia].

- At that moment both the Ukrainian military units and the Bolsheviks’ forces meant the same for the Czechs – as both were new political powers whose activities were directed against the Provisional Government: Vojenský historický archiv Vojenského ústředního archivu [VHA VUA - Military Historical Archive of the Central Military Archives, Prague, Czech Republic], OČSNR v Rusku – presidium [OCSNR in Russia - presidium], 1917-1918, box 6, sig. 2703. Presidium komisi. V Kyjevě 18.11.1917. Dopis I.Kudely [Presidium of the commission. Kiev 18 November 1917. Letter I. Kudely], p.3.

- The Czechs were the only military force in Kiev, which was allowed to guard the most important urban objects by both the Ukrainian and the Bolshevik authorities. Thanks to them the dwellers had electricity and water despite military conflicts. Indeed, they were the only military authority which could guarantee safety for the electric station, spirituous fabric, water supply, warehouses. However, OCSNRR refused the Council of Landlords Society’s and rectors of Kiev Polytechnic appeals to delegate the legions to guard Kiev against looters: VHA VUA, První česko-slovenský střelecký pluk. Rozkazy [The First Czechoslovak rifle regiment. Orders], book 11. 1917-1918. Приказ по 1-му Чешско-Словацкому [The order to the 1st Czechoslovak rifle regiment]; VHA VUA, OČSNR v Rusku – presidium [OCSNR in Russia - presidium]. 1917-1918, box 6, sig. 4093. Presidium OČSNR, Kijev 24.01.1918. č. 3747. стрелковому «Яна Гуса» полку, № 1252. 5.02.1918 [Presidium OCSNR, Kiev 24 January 1918, c.j. 3747 to Jan Hus rifle regiment, No. 1252, 5 February 1918]; VHA VUA, OČSNR v Rusku – presidium [OCSNR in Russia - presidium]. 1917-1918, box 23, 1918. Zapísy schůzí. Leden-únor. Opisy. [Records of the meetings. January-February. Descriptions], sig. 28. Protokol presidiální schůze konané 24.01.1918 [Minutes of the Presidium meeting held on 24 January 1918], sig. 29. Protokol presidiální schůze konané 25.01.1918 [Minutes of the Presidium meeting held on 25 January 1918].

- AMZV, box 6, sig. 2703. Митинг угнетенных и расчлененных народов [The meeting of the oppressed and divided nations], p. 2.

- VHA VUA, První česko-slovenský střelecký pluk. Rozkazy [The First Czechoslovak rifle regiment. Orders], book 11. 1917-1918. Приказ по 1-му Чешско-Словацкому [The order to the 1st Czechoslovak rifle regiment]; VHA VUA, OČSNR v Rusku – presidium [OCSNR in Russia - presidium]. 1917-1918, box 6, sig. 4093. Presidium OČSNR, Kijev 24.01.1918. č. 3747. стрелковому «Яна Гуса» полку, № 1252, 5.02.1918 [Presidium OCSNR, Kiev, 24 January 1918, c.j. 3747 to Jan Hus artillery regiment, No. 1252, 5 February 1918].

- VHA VUA, První česko-slovenský střelecký pluk. Rozkazy [The First Czechoslovak rifle regiment. Orders], book 11. 1917-1918. Приказ No. 1241; Приказ No. 1252 [Order No. 1241; Order No. 1252].

- M. Bulgakov, The White Guard, trans. M. Glenny with an epilogue by Victor Nekrasov, New York - St. Louis - San Francisco 1971, pp. 56-57.

- Glinka, W cieniu cit., p. 236.

- Švihovský, Kijev a kijevští Češi cit., p. 153.

Bibliography

Primary sources

Unpublished:

Archiwum Akt Nowych w Warszawie (AAN) [Nation Archive, new funds, in Warsaw]

-Akta Romana Knolla

-Organizacje polskie w Rosji

Archiv Ministerstva Zahranicnich Veci (AMZV) [Archives of Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Prague]

-Sibirsky archiv

-Korespondencja

Vojensky historicky archiv Vojenskeho ustredniho archive v Praze [Military Historical Archive of the Central

Military Archives in Prague]

- OCSNR v Rusku – presidium. 1917-1918.

- Prvni cesko-slovensky strelecky pluk. Rozkazy

Published:

Ambroz V., Cesi a Slovaci v Rusku [Czechs and Slovaks in Russia], in Nase zahranici. Sbornik Narodni rady ceskoslovenske, 1922, vol. 3, No 3, pp. 97-100.

Bulgakov M., The City of Kiev, Id., Notes on the Cuff and Other Stories, Ann Arbor 1991.

Bulgakov M., The White Guard, trans. Glenny M. with an epilogue by Victor Nekrasov, New York - St. Louis - San Francisco 1971.

Glinka X., W cieniu Złotej bramy [In a shadow of the Golden Gates], in Pamietnik Kijowski, vol. I, London 1959, pp. 209-236.

Gunther W., Polski teatr w Kijowie [Polish theater in Kiev], in Pamiętnik Kijowski, vol. III, London 1966, p. 194-199.

Kovařík F., Dr. Václav Vondrák padesátníkem, in “Příloha ‘Věstníku Ústředního Sdružení Čechů a Slováků z Ruska”, 1930, X, 5.

Rejman Z., Dr. Vondrák pokrokovec – nebo reakcionář? in “Přiloha ‘Věstníku Ústředního Sdružení Čechů a Slováků z Ruska”, 1930, X, 5. pp. 2-3.

Švihovský V., Kijev a kijevští Češi [Kiev and Kievan Czechs], in Naše zahraničí. Sborník Národní rady československé, vol. IV, No. 4. pp.152-163.

Walewski S., C.K.O. w Winnicy na Podolu [C.K.O. in Vinnytsia in Podole], in Pamiętnik Kijowski, vol. III, London 1966, pp. 149-157.

Грушевський М., Хто такі українці і чого вони хочуть [Who the Ukrainians are and what they want], in Політологія: кінець ХІХ – перша половина ХХ ст. Хрестоматія, Lviv 1996, p. 178-189.

Перепись г. Киева 16 марта 1919 г. Ч. 1: население, Kiev 1920, tabl. ІІ. [Census in Kiev, 16 March 1919. Part 1: population]

Ходорович Н., Пламенный патриот (Из воспоминаний о д-ре В. Вондраке) [Sincere Suppoter (from the memories on dr. V. Vondra)] in “Přiloha ‘Věstníku Ústředního Sdružení Čechů a Slováků z Ruska”, 1930, X, 5, p. 5-6.

Secondary references:

Bradley J.F.N., The Czechoslovak Legion in Russia, 1914-1920, New York 1991.

Certeau M. de, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Rendall S., Berkeley - Los Angeles 2002 [first published as L’Invention du quotidien, vol. 1, Arts de Faire, Paris 1974].

Hašek J., Osudy dobrého vojáka Švejka [The Good Soldier Švejk], Bratislava 2000 [first published in 1921-1923 in Prague].

Jabłoński H., Polska autonomia narodowa na Ukrainie 1917-1918 [Polish national autonomy in Ukraine 1917-1918], Warsaw 1948, p. 36.

Kappeler A., ‘Great Russians’ and ‘Little Russians’: Russian-Ukrainian Relations and Perceptions on Historical Perspective, in The Donald W. Treadgold Papers in Russian, “East European, and Central Asian Studies”, October 2003, 39, p. 72.

Liczebność Polaków na Rusi na przełomie w. XIX i XX [The quantity of the Poles in Rus’ between the 19th and 20th centuries], in Pamiętnik Kijowski, London 1959, t. I, pp. 86-90.

Lynch K., The Image of the City, New York 1960.

Mądzik M., Z działalności Kijowskiej Rady Okręgowej Polskich Towarzystw Pomocy Ofiarom wojny w latach I wojny światowej [From the activities of the Regional Kiev Council of the Polish Society for Supporting war Victims during World War I], in Pamiętnik Kijowski [Memories of Kiev], vol. VI, ‘Polacy w Kijowie’, Kiev 2002, pp. 177-195.

Nazwa geograficzna. Rozpatrywany obszar [Geographic name. Defined region], in Pamiętnik Kijowski, vol. I, London 1959, pp. 9-10

Nicieja S., ‘Polski Kijów’ i jego zagłada w latach 1918-1920 w świetle wspomnień kijowian [‘Polish Kiev’ and its death], in “Przegląd Wschodni”, 1992/1993, II, 4 (8), pp. 851-862.

Pietrow-Ennker B., Ulianova G. (eds.), Civic Identity and the Public Sphere in Late Imperial Russia, Moscow 2007.

Sennett R., The Uses of Disorder: Personal Identity and City Life, New York, 1971,

Sopicki S., Omówienie pracy Jana Korneckiego ‘Oświata Polska na Rusi w czasie wielkiej wojny światowej’, in Pamiętnik Kijowski, vol. I, London 1959, pp. 198-205.

Šteidler F., Československé zahraniční vojsko [Czechoslovak army abroad], in Československá vlastivěda. Stát, Prague 1931, vol. V, pp. 556-581.

Vaculík J., Dějiny volyňských Čechů [The History of the Volhynian Czechs], Prague 1998, vol. II.

Wierzbicka A., Understanding Cultures through Their Key Words: English, Polish, German, and Japanese, New York - Oxford 1997

Winter J., Robert J-L. (eds.), Capital Cities at War: Paris, London, Berlin 1914-1919, Cambridge 1997

Wrzosek M., Polski czyn zbrojny podczas Pierwszej wojny światowej: 1914-1918 [The Polish millitary action during the First World War: 1914-1918], Warsaw 1990, p. 377.

Бовуа Д., Битва за землю в Україні 1863-1914. Поляки в соціо-етнічних конфліктах [La Bataille de la Terre en Ukraine 1863-1914. Les Polonais et les conflits socio-ethniques], trans. Boryssiouk Z., “Критика” 1998.

Верстюк В., Українська Центральна Рада [Ukrainian Central Rada], Kiev 1997, p. 208.

Драгомирецкий В., Чехословаки в России 1914-1920 [Czechoslovaks in Russia 1914-1920], Paris - Prague 1928.

Луцький Ю., Чехи на Україні (1917-1933) [The Czechs in Ukraine (1917-1933)], in “Хроніка 2000: Чехія”, [Chronicle 2000: Bohemia], Kiev 1999, vol. 29-30, t. II, p. 119.

Савченко Г., Польські військові формування у Києві у 1917 р., in Pamiętnik Kijowski, vol. VI, Polacy w Kijowie, Kiev 2002, p. 220.

Татаров-Альберт Б., Драматичні сторінки історії [Dramatic Pages of History], in “Хроніка 2000: Чехія”, [Chronicle 2000: Bohemia], Kiev 1999, vol. 29-30, t. II, pp. 272-284.

Illustrations from Catalogue J, Detroit Publishing Company, 1905: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Photochrom Collection: Fig. 1, ppmsc 03830; Fig. 2, ppmsc 03825; Fig. 3., ppmsc 03829; Fig. 4, ppmsc 03817; Fig. 5, ppmsc 03812; Fig. 6, ppmsc 03818; Fig 7., ppmsc 03823; Fig. 8, ppmsc 03819.

OLENA BETLII. Ubi bene ibi patria: Reading the City of Kiev through Polish and Czech “Spatial Stories” from the First World War Period.

There is a saying: “A city is more beautiful than a village, because it is rich with people’s history”. Kiev is a good illustration of this statement. Just like other cities, it was inhabited with the spatial stories of its occupants. Although wartime had a significant influence on the life of Kiev’s inhabitants, the city continued to model and construct their urban life. It consisted of different elements which made the activities of the Polish and Czech communities possible. They lived their lives through familiar paths, landmarks, and edges which were established in the pre-war period. The Polish and Czech newcomers did not reformulate the local urban identity that they encountered upon their arrival. They only enriched it with new recognizable signs and meanings.

Abstract

This chapter focuses on Kiev during the upheavals of the First World War period by

analyzing Czech and Polish ‘spatial stories’ of the city. It examines the effect of the war

on the everyday pursuits of pre-war Kievites of Czech and Polish origin and new arrivals

to the city. The author ascertains whether and how their perception of Kiev was

transformed during the war: from home into lost space. It is argued that Kiev played an

important role in the development of the daily activities of Czechs and Poles and that,

furthermore, both ethnic groups influenced the city by filling it with their own spatial

practices, thereby formulating a unique identity for the city that bore special significance

for its migrant communities.

Вважається, що місто гарніше за село, оскільки воно збагачено людською історією.

Правдивість цієї тези можна легко підвередити на прикладі історії Києва. В даній

статті увагу зосереджено на міській історії впродовж Першої світової війни та на

використанні міського простору чехами і поляками. Використовуючи методологіч-

ний інструментарій Мішеля де Серто, зроблено спробу віднайти те мистецтво ре-

акції на виклики повсякдення, яке продемонстрували згадані етнічні спільноти про-

тягом воєнних років. У статті показано послідовність зміни використання міста

– від домівки-вітчизни до втраченої території. Це відбувалося крізь призму творен-

ня свого власного простору, прочитання міста крізь наділення його об’єктів та про-

стору значеннєвими кодами. Впродовж війни попри те, що чеська і польська спіль-

ноти значно збільшили свій кількісний та змінили свій якісний склад, сприйняття

міста, його ідентичність не змінилися, однак вони щезли разом із їхніми творцями.

У статті простежено просторові історії та виокремлено просторові практики,

сповнені особливої пам’яті, що поділялася усіма чехами та поляками Києва. Вій-

на змінила значення деяких об’єктів міста, готелі якого були переоблаштовані під

офіси та місця політичних зібрань, публічні приміщення, цирк, стали свідками ви-

датних конгресів, монастирі та університет відкрили свої терени для формування

не своїх військових підрозділів (Чеської дружини). Це лише перша спроба прочитати

Київ крізь просторові історії його мешканців, прояв спокуси затримати на довше

блимання вогника, який у вигляді ностальгійних спогадів дозволяє нам відчути себе

в постаті тих, чиї давно зниклі кроки оживляли Київ.

Introduction

You can meet in the streets of Prague a shabbily dressed man who is not even himself aware

of his significance in the history of the great new era. He goes modestly on his way, without

bothering anyone. Nor is he bothered by journalists asking for an interview. If you asked

him his name he would answer you simply and unassumingly: ‘I am Svejk’1.

That is how the prominent Czech writer Jaroslav Hasek pulled an anonymous inhabitant

out of the embrace of the street, introduced him and forced us to follow his steps,

to read his ‘spatial stories’, during the 500 pages of his book. Reading this novel, one

actually does what Michel de Certeau wanted all of us to do– to understand the subject

in space while reading his or her own spatial stories. I consider Svejk’s urban experience

– ‘the murmuring voice of societies’ – to be a good way of demonstrating de Certeau’s

technique, but what can we say about Hasek in this context?

A building on Volodymyrska Street in downtown Kiev bears a plaque with the inscription:

“Jaroslav Hasek, a famous Czech writer, lived here during the World War I”. This

is the only name that has been commemorated out of almost 50,000 Czech and Slovak

people in Ukraine. A large part of this community marched through Kiev in the late

winter of 1918 leaving the city for Prague via Vladivostok. However, my task here is not

to write a story about Hasek, but rather to produce, or else find, de Certeau’s “science

of singularity”2 – a science of the relationship which linked the everyday pursuits of the

inhabitants to the particular circumstances of World War I in Kiev. Thus, my intention

is to show how culture – “a system of inherited conceptions expressed in symbolic

forms by means of which people communicate, perpetuate, and develop their knowledge

about and attitudes toward life”3 (Clifford Geertz) – was consumed by ordinary

Czech and Polish men far from their homeland, in their new Heimat – a Ukrainian

metropolis. This kind of approach helps avoid the pitfalls of nationally oriented studies,

which still prevail in Ukrainian, Czech and Polish historiographies. The authors of

Capital Cities at War: Paris, London, Berlin 1914-1919 demonstrated that the history

of World War I can be better understood if one investigates its events through urban

studies, paying attention to the metropolis as the “social formation at the juncture between

the national state and civil society, as defined by collectivities of many kinds”4.

Following their approach, this chapter will not focus on the urban level of waging war

but rather on the urban activities of an under-researched collection of city-dwellers,

namely minority ethnic groups. Specifically this study is concerned with the Czech and

Polish indigenous population and new arrivals, who together transformed Kiev into an

immigrant city by 1917.

The specific questions I will ask below, in terms of the ‘science of singularity’ framework,

are: How did the Czechs and Poles perceive Kiev? Where did they concentrate

and how did they inhabit the city space? What did their daily routes look like? Where

did they start and end? Which places bound these ethnic groups together through

common memories? How much did the War influence the usual traditions of city life

and reformulate urban identity? In this article I attempt to answer these questions by

examining them in terms of the key formula – Ubi bene ibi patria5. Research of this

kind can reveal an interesting and rare phenomenon in urban history, when a city’s fate

depended not on the indigenous population, but on the newcomers who came to the

city as refugees, rather than permanent occupants.

Kiev as Heimat

Polish colonization of Ukrainian territory began several centuries before the start of

Czech colonization. The former can be traced back to 1569, when Ukrainian lands became

an integral part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The latter was mainly

rooted in late 19th century Pan-Slavist sympathies. Nevertheless, one should not forget

that the first Czech colonists appeared in Ukraine soon after the defeat of Czech

rebels in the battle of Bila hora [White Mountain] in the first half of the 17th century.

Despite this, before World War I both ethnic communities6 considered the land where

they had settled as their motherland, their home, and a place of safety. They took root

in these lands and filled them with their own memories and stories. “We were the citizens

of this land, which owes everything to us”, Polish colonists in Ukraine used to say

(a statement echoes the discourse of colonialism worldwide)7. The status of Czechs and

Slovaks differed slightly; it may be summarized as follows: “in the harsh conditions of

the Russian Empire, most of them had lost interest in their native country and its problems,

becoming thoroughly Russified”8. The best expression of the migrants’ identification

with the Ukrainian lands was conveyed by the name which both the Polish and

the Czech communities used to designate Ukraine: they called it Rus’ (referring to the

medieval state Kievan Rus’) and its native population, Rusyny (Ruthenians). The Czech

colonists probably adopted the name Rus’ from Poles9, who wanted to emphasize their

own, rather than Russian, legacy and tradition in these lands10. But the question is how

much these attitudes were preserved within the city walls. If Ukrainian lands were perceived

as a homeland, what role did Kiev play for these ethnic groups?

There are many starting points from which to answer the questions mentioned above

and, in this way, to read the Czech and Polish spatial stories of Kiev. If we give the floor

to a flaneur, we can see that the description of a city naturally begins with an edge: “I

see my city picturesquely situated on the right bank of the Dnieper… I see this city

immersed in the green beauty of the charmed parks that embellish the hills under the

river bank…”11. As in this quotation, the Dnieper, which divides Kiev into two parts,

was the line from which the Poles and the Czechs customarily drew their map of the

city. But the river bank did not expose “an entire metropolis to view”12, as Lake Michigan

in Chicago did in Kevin Lynch’s classic example of the edge, without which the

city cannot be pictured13. Rather, it marked the developed part of the city and created

a beautiful cityscape visible from the non-urbanized opposite bank of the river, where

the first recreation districts began to appear at the turn of the 20th century. The river

bank also had another function. It was the end of the usual path, which led a flaneur to

the main cultural events that took place in the city and were organized in the numerous

parks and districts along the Dnieper, for example, in the Kupetski Sady (Merchants’

Gardens) or in the trade area in Podil. One could enjoy concerts, dances, talks, singing,

playing cards, and flirting there. It was the most romantic part of Kiev and an area that

encouraged a feeling of belonging. This kind of spatial practice neglected all differences

between city-dwellers. However, these differences surfaced immediately after leaving

this area. They arose when visitors returned along the routes that had led them to the

river bank. Thus, at this stage we come to another possible starting point in our attempt

to read the urban space, which may be narrated as follows: “Let us take a tour from the

edge in summer 1914” or “Were we to follow one of the residents along her typical

route to the Dnieper, the experience would be something like this”14.

Fig. 1

View at Podil.

The task is not easy, however. Ordinary people of Czech and Polish origin left so little

evidence of their city life that one may only guess at how their itineraries were organized.

The sources that remain allow us to reflect on how urban space was occupied by

communities in general, rather than how they articulated their social differences using

the urban landscape. Indeed, in this case Kiev becomes fragmented into different parts,

the histories of which can unfold “like stories held in reserve”15. To evoke these stories

let us take a closer look at the city in general. By the beginning of World War I Kiev was

one of the most pleasant cities in the Russian empire. Under the influence of the new

industrial age, the city had expanded rapidly. New multistoried houses with apartments

for rent were built everywhere; a regular water supply became standard across the city

centre; new roads were paved; electric lights replaced the old gas lights along the streets;

and tramlines connected the city centre with outlying areas. All this made Kiev increasingly

attractive to businessmen, traders, and craftsmen. Also, by the end of the century

it became an important educational centre. These changes caused an increase in the

city’s population. Part of this population growth was made up of the two ethnic groups

we are interested in. Between 1897 and 1914 the Polish population grew from 35,552

to 60,000 (the total population of the city on the eve of the War was 600,000)16. Kiev

also became attractive to the Czechs. In 1909 the young Czech community comprised

as many as 3,000-3,500 members17.

The industrial age finally defined the functions of the city districts. ‘Little Paris’, as people

sometimes called Kiev at the time, received its newly restored and very wide street,

Khreshchatyk, which became the main artery of the city. Its appearance was shaped by

numerous hotels, stores, restaurants, cafes, and business offices. At the same time it was

also the place for everyday strolling. It was beautiful, and attractive to those who had

capital and wanted to start a new business in the city. So, taking into account that the

Poles were the richest landlords in this part of the Russian Empire, it is not surprising

that there were a large number of Polish landmarks on the Khreshchatyk. On this street

one could find Marszak’s jeweler, Fruzinski’s cafes and Idzikowski’s bookstore and library18.

The latter was well known in the Russian Empire and in Europe for its rich collection

of music literature. In another district one could find the musical instruments

store which belonged to local ‘Czech king’, Jindrich Jindrisek. The intellectual district

was also nearby, marked by St. Volodymyr University, the Second Gymnasium, the Opera

House, and the City Theatre, all of which were located along Volodymyrska Street.